The camouflaged military truck sped across the dirt and mud in near silence. The only noise was a low air-compressor whine and the crunch of tires through the rough terrain.

This futuristic pickup – a modified Chevrolet Colorado – runs on electricity generated by a hydrogen fuel cell. The zero-emissions truck is the result of a $4-million partnership between General Motors and the U.S. Army to determine whether hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are ready for the combat zone.

GM brought the truck, code-named ZH2, to its proving grounds in Milford, Mich., on a windy March afternoon to demonstrate the pickup’s capabilities.

The ZH2 will soon be delivered to the Army for testing. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles have the potential to offer greater range, fuel efficiency and noise reduction than the diesel-powered trucks currently in use.

In this test, the off-road truck, based on the Colorado ZR2, demonstrated that it brings new-age efficiency and ample muscle to the front line. More than 1,000 pound-feet of torque provided brisk and consistent acceleration. Like the ZR2, it can scale soggy moguls and romp down steep descents with ease. Even at high speed over gravel and gopher holes, the ZH2 is stable and smooth.

“The vehicle can power through that, unimpeded by the terrain, and you’re doing it efficiently,” said Charlie Freese, director of GM Global Fuel Cell Activities. “We’re doing it with more than twice the efficiency of the internal combustion engine.”

The vehicle has four radiators, and various parts from Chevrolet’s Camaro and Corvette. Except for the stock Colorado doors, all body panels are made of carbon fiber infused with Kevlar.

Chevrolet ZH2. (Photo: Ryan ZumMallen/Trucks.com)

The ZH2 has a top speed around 70 mph and peak range around 200 miles, but is capable of much more, Freese said.

GM used an older-generation fuel cell system in the ZH2 because it had proven capability in more than 3 million miles of testing. The company is currently working on systems that are smaller, quieter, more powerful and more affordable.

“This is already a stable system, so we know how it performs,” Freese said. “This one’s good. The next one’s fantastic.”

Reporting for Duty

Hydrogen “really provides flexibility and options because we can produce it from any number of ways,” said Brian Butrico, chief engineer at the U.S. Army Tank Automotive Research, Development and Engineering Center, or TARDEC.

Hydrogen can be produced from a variety of sources, such as natural gas and fossil fuels, or renewable energy such as wind and solar power.

The Army wants to learn if it can transition to hydrogen fuel from JP-8 – a form of diesel that powers tactical vehicles and generators.

It is enticed by the potential benefits of the ZH2 fuel cell system, Butrico said. Its only emission is water. In a pinch, it could provide water to soldiers at a rate of two gallons per hour. The Exportable Power Take-Off unit loaded in the truck bed can be removed and used as a mobile generator with 25 to 50 kW of power.

“That’ll run a subdivision,” Freese said.

The military has long been interested in hydrogen fuel cell technology. As far back as 1995, the Department of Defense deployed fuel cell vehicles around the world for testing. TARDEC ordered and tested a number of Ford Escape fuel cell vehicles for years in the late 2000s. GM is currently working with the U.S. Navy on an unmanned underwater vehicle powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

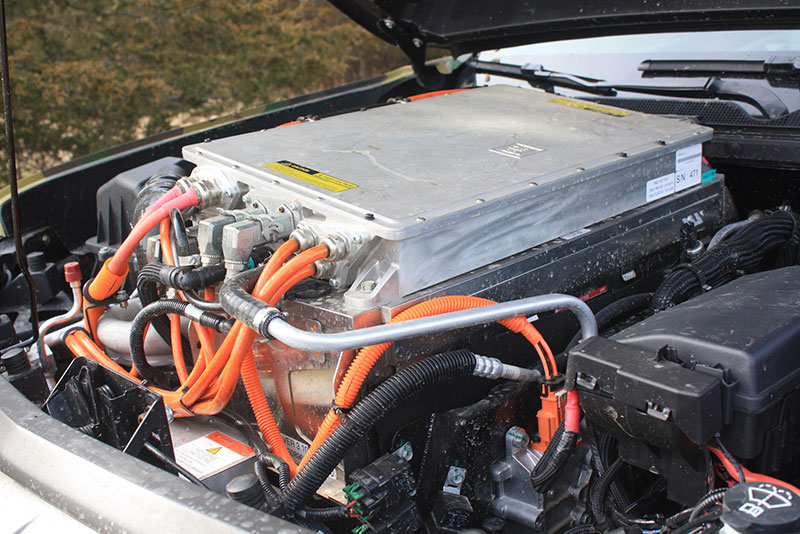

The fuel cell system inside the ZH2. (Photo: Ryan ZumMallen/Trucks.com)

“It’s really evolved to be a vehicle that is quite impressive,” said Scott Samuelsen, director of the National Fuel Cell Research Center at the University of California, Irvine.

The ZH2 itself is not likely to make its way into military fleets. The Army, however, is serious about implementing hydrogen fuel cell technology on the battlefield as soon as possible, Butrico said.

The Army will take delivery of the ZH2 on April 10. The truck will spend several months at different bases around the country, each one providing new challenges and testing scenarios. After one year, the military will evaluate the tests and decide how to proceed.

“If there’s one thing our guys are good at, it’s breaking stuff,” said Doug Halleaux, a TARDEC spokesman.

How the ZH2 responds to Army testing will determine the next steps.

“Really it’s what do the soldiers think about it?” Butrico said.

Finally Time to Shine?

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles also are starting to show up in the civilian light vehicle market. Automakers are investing heavily in technology as they work to meet increasingly stringent emissions standards.

A 2014 report by research firm Frost & Sullivan predicts that nine automakers will produce hydrogen fuel cell vehicles by 2020. General Motors has logged more than 3 million miles of testing its own hydrogen fuel cell vehicles and is partnered with Honda on further development

Nick Loris, analyst at the Heritage Foundation, has in the past been skeptical of government investment in alternative fuels. The Department of Defense has been mandated to spend public money on renewable energy for political reasons, Loris said. But if the military now sees a practical purpose for hydrogen fuel cells, that’s different, he said.

“If it makes sense for the military and Department of Defense to invest in alternative fuels and it increases their operational readiness, or increases their capabilities and improves their missions, then that makes all the sense in the world,” Loris said.

“The more we can rely on the private sector for those things; you’re not creating a market out of thin air. You already have the developed technology, so that’s certainly an added benefit.”

Butrico said he can see hydrogen fuel cell technology in military vehicles within the next five years. He said hydrogen fuel cells could feasibly provide supplemental power to even a 30-ton Bradley tank.

But the first step, he said, is the ZH2.